Missing the Mark: Portrayals of the Black Body in 20th-Century Latin-American “Modernism”

At the dawn of the 20th century, modernism arose as the primary mode through which to transcend traditional European academic art. Fundamentally an avant-garde movement, modernism allowed for the investigation of taboo subjects, many of which were captured by Latin American artists. Defying European artistic standards, these Latin American artists exploited stylistic approaches to modernism; then, they developed various nuanced approaches to established sub-movements of modernism. Some artists referred to their work as a “cannibalism” of European art—that is, the method of “eating” up what they liked about certain practices and “sacrificing” what they didn’t.

Within these movements, Black people provided a creative muse for several non-Black artists from the Americas. Black people, however, were often viewed as exotified subjects, and the use of nudity of predominantly Black women functioned as a means to fetishize their supposedly alluring or bizarre features and figures. Exploiting the black body, then, these artists seized the concept of modernism for personal advancement in the art world. To this end, it’s vital to question whether their crafted notion of modernism was really modernism at all. That is, if the purpose of modernism in the 20th century was to expose social realities and raw humanity, can many Latin American artists’ caricatured, sometimes even sexually provocative, renderings of Black people qualify as examples of this new artistic movement?

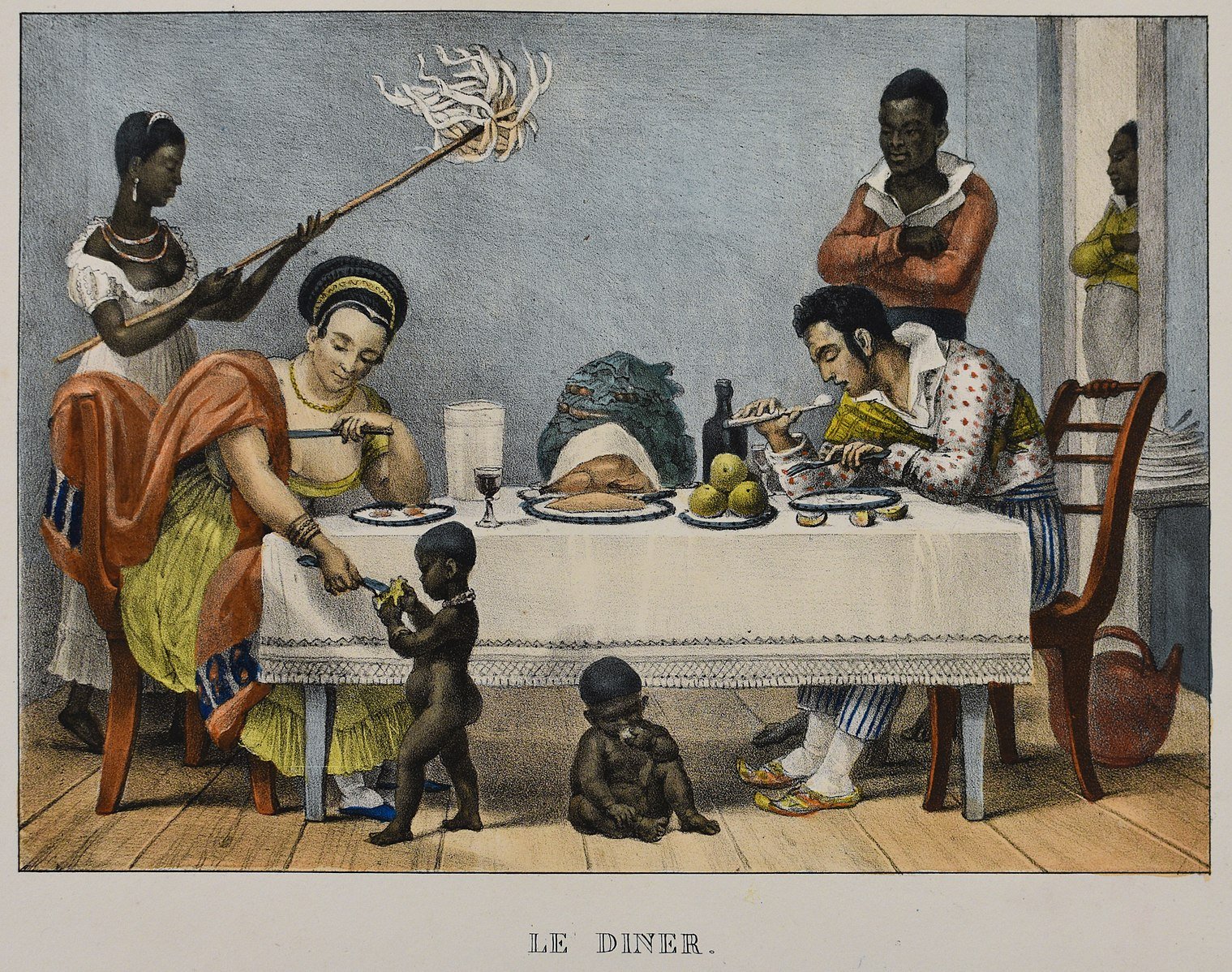

The origins of artistic colonization (how the exotification of Black people through modernism should be understood) extend much before the modernist movement. A Brazilian Family in Rio de Janeiro (1839) by Jean Baptiste Debret, a French, non-Black painter, should be positioned and analyzed in a European context, which placed idealized Western values at the forefront of artworks and gave little regard to truthful depictions of Latin America and its native people. During the mid-19th century, non-Black people (often of Portuguese descent, as Portugal colonized Brazil centuries prior) often owned Black slaves.

Debret’s painting is portrayed in a traditionally academic style, with a visually-pleasing color palette that creates a balanced mix of cool and warm tones. The most striking contrast in color, however, is between the fair, porcelain skins of the elite man and woman, and their slaves’ skins, which are a deep, nearly black shade of brown. A power dynamic exists between the seated white man and woman enjoying their meal at the heart of the painting and their three slaves and two infants, who are placed at the periphery of the canvas.

Debret, Jean Baptiste. A Brazilian Family in Rio de Janeiro. 1839, Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brasil.

In this piece, Blackness is not only an assignment of color but a role to play, one in which an exotified subject exists only to serve and somehow advance the pictorial narrative of the non-Black person. This conjecture is supported by the actions performed by each slave in Debret’s painting: the Black woman in the left corner provides relief from heat to the white couple with her feathered fan, two Black men in the right corner patiently anticipate commands from the couple, and two nude, Black infants eagerly accept morsels of the white woman’s food, a suggestion of the white slave owners’ generosity.

An insistence on the slave owners’ benevolence similarly informs the painting’s rhetorical project, reflected through the clean, unfettered clothing donned by each slave (especially the woman, with her elegant white dress and jewelry) and the infants’ well-fed bodies. There is no clear criticism of the power dynamic established in the piece, only an assertion of an idealized structure of roles belonging to Black slaves and white slave owners/colonizers. The painting is propaganda, and this propaganda is easy to understand: the relationship presented in this piece between Black slaves and their masters is mutualistic; jovial, even. The ignorant and detrimental absence of nuance in A Brazilian Family in Rio de Janeiro should be what distinguishes it from the more introspective strokes of modernism, yet this is hardly the case when we compare this old relic to modernist pieces which view Black people as smiling puppets or sexual props.

Let us shift to our first example of 20th-century artistic exploitation of Blackness: Candombe (1925) by Pedro Figari, a non-Black Uruguayan artist.

Figari, Pedro. Candombe. 1925, Uruguay.

Figari’s fascination with Afro-Uruguayans was largely based upon his attribution of Blackness to their stereotypically provocative music and dance traditions, all of which contributed to the Latin American appropriation of otherness. Even if his intentions were to convey a sense of celebration of national identity or nostalgia (which could also be associated with historical performances of ethnicity before audiences), Figari’s inclination to depict Black people dancing with glee amongst each other may have been rooted in primitivism.

The rhythm and syncopation of dance linked the Black body with the primitive, situating Figari’s caricature as a testament to racist iconography rather than as an inventive method of depicting anatomical features. In stark contrast, the works created by modernist Black artists thematically reimagined the visual codes typically attributed to the Black body during the early 20th century. In these paintings, subjects participate in the mundane activities of everyday life: loving, touching, crying, singing, laughing.

Afro-Uruguayan slaves had been emancipated by the time of this painting’s creation, but continued to suffer from racial discrimination in Uruguay; this racism often took the form of artistic fetishization, particularly in reference to stereotypes of dance and music. Objectively, Figari’s painting follows the modernist style in its lack of depth, vibrant use of color, visible brush strokes, and representation of “everyday life”—or, rather, a shallow perception of it. In terms of subjectivity, however (which is thematically vital to modernism as a movement), there is none: Figari’s portrayal of Afro-Uruguayans is one-dimensional in its understanding of culture and limits Black potential for sensitivity, intellect, or depth. While they are not enslaved, they exist solely for a commodified purpose (in this case, one of entertainment), similar to the slaves depicted in Debret’s A Brazilian Family in Rio de Janeiro whose Blackness relegates them to a life of service to non-Black elites.

Prominent among the objectification of Black people was the sexualization of Black women. An example is A Negress (1923) by Brazilian Cubo-Futurist artist Tarsila do Amaral, created during the rise of the avant-garde in Latin America. In this piece, the entire pictorial space is utilized, as the dominant figure in the foreground occupies most of the canvas in a warmer tone yet leaves space in the background for darker hues that seem to dramatically emphasize the figure’s presence. Although this work is a painting, its composition (containing certain overlapping elements) gives it a collage-like effect; consequently, some elements seem closer to the viewer than others. Round, shaded shapes are used in the foreground, contrasting with the succinct horizontal and diagonal lines in the background. The woman presented in the piece does not seem completely human, but instead distorted and caricatured. Savage, even.

do Amaral, Tarsila. A Negress. 1923, Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo.

By her dark skin color and stereotypically enlarged lips and nose, it’s assumed that this woman is Black. Her diagonally-inverted eyes similarly add to her intense, direct gaze is a common modernismo technique. Her anatomically disproportionate hand and large feet are relaxed like the rest of her body, and one of the woman’s bare breasts rests in front of her forearm. Her legs are twisted around each other to an impossible extent, and her torso is unrealistically short. An abundance of green in the background suggests a serene and natural setting, and the woman lacks hair, which accentuates her round, voluptuous bodily composition.

At the time that A Negress was produced, slavery had been abolished in Brazil, but Black people nevertheless remained a target for racism and exploitation throughout the country; more specifically, Black women faced sexualization and fetishization by non-Black artists in the interest of taboo, exotic modernismo success. Perhaps it was not do Amaral’s intention to portray her Black subject in a caricatured and thus racist mode but instead to express her knowledge of Candomble statuary of Afro-Brazilian deities. This hypothesis, however, should be critiqued, as the woman’s features are enlarged and arguably sexualized as her bare breast is an unequivocal focal point of the painting. Although the female figure is objectified in this piece, she can also be perceived as formidable—physically, by her broad shoulders, hearty physique, and strong, upright posture—but perhaps spiritually too, as is conveyed through her unwavering eye contact with the viewer and self-assured expression.

While she is viewed in Brazil as socially inferior due to her ethnicity and gender, the woman in do Amaral’s painting seems to maintain her confidence and composure, asserting her presence and humanity despite her ethnically-assigned status and vulnerable nude state. The banana leaf in the background is reminiscent of the land on which Afro-Brazilian slaves were forced to work before their emancipation; however, the woman assumes a resting position instead of actively working. This could, in some ways, symbolize her independence or potential for agency.

Independence and agency are two factors that, if employed with liberty—not racism—by artists like Figari and do Amaral, could have contributed to a much more nuanced, just, and genuine depiction of the Black body in Latin American art throughout the modernist period.

To be sure, there are notable examples of Black artists’ portrayals of Black life, culture, and resistance. Formally, modernist works by both non-Black as well as Black artists shared several characteristics, including a lack of deep space, the use of a direct gaze, experimentation with color, and Impressionist understandings of subject matter. Perhaps the most striking example of such is Negro Aroused (1935), Edna Manley’s sculpture of a Black male figure that represents Jamaican strength under the oppression of British colonialism.

Manley, Edna. Negro Aroused. 1935, National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston.

The physical formidability of Manley’s piece draws not only upon the Egyptian sculptural tradition but of the vigorous persistence of Jamaican identity: as accounted by David Boxer, Negro Aroused was “nothing less than the icons of that period of our history, a period when the Black Jamaican was indeed aroused, demanding a new social order, demanding his place in the sun.” Indeed, the latter comment made here is formally evident. The figure faces upward, as if turning a blind eye against poverty and indentured servitude and toward freedom, hope, rebellion. Negro Aroused is a work of solidarity, not of exoticism: it fulfills modernist ideals of raw humanity while drawing upon understood inspiration to the artist. Created during the empowering era of Marcus Garvey and the movement for Pan-Africanism, the piece’s social function transcended biennial success and monetary value: ever since its production, it has remained a symbol of equality and human rights for Jamaican people.

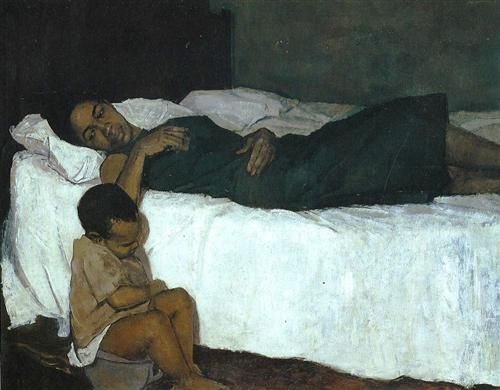

Watson, Barrington. Mother and Child. 1958-59, National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston.

Reflecting the predominance of quotidien subject matter and social realism, Jamaican artist Barrington Watson’s Mother and Child (1958-1959) similarly offers a scene of everyday life while simultaneously asserting Black humanity.

The Black mother’s body is not sexualized in this painting, and is instead in repose and fully clothed as she gazes affectionately at her young child beside her. The child is not fully clothed, and sits on a toilet with his back turned against the viewer and toward his mother. Absence of clothing here is not sexual; instead, it is used to portray an essential bodily function. The essence of modernity’s approach to everyday life is exemplified in earnest through this piece. Here, the Black woman is not a fetishized object but rather an intimate symbol of raw experience and caregiving, painted in muted tones against a starkly white bed covering.

. . .

The Black body is not exotic. It is not to be objectified when dancing, when working, when nude; racial exploitation exemplified by many Latin American artists was not only harmful to a liberation and abolition movement they should have cohabited, their oeuvre missed the mark of the Latin American approach to modernism.

Latin American artists resolved to cannibalize European art at the turn of the 20th century, to consume and practice modernist techniques of which they approved and sacrifice the remains. The selfish, racist, and greedy approach to Latin American modernism that artists such as Pedro Figari and Tarsila do Amaral pursued focused not on an egalitarian, social-realist depiction of Black people. It instead objectified them for the artists’ own benefit: when compared to earnest depictions of Black culture or political/social position (such as modernist works by Edna Manley or Barrington Watson), the “exotic” works of Black individuals produced by Latin American artists were not revolutionary in their cannibalism. They were gluttonous.