Is Everything Okay?: Revisiting Mental Illness on Tumblr and TikTok

Content warning: This article contains mentions of eating disorders, self-harm, suicide, and other mental health disorders. Resources can be found at the bottom of the article.

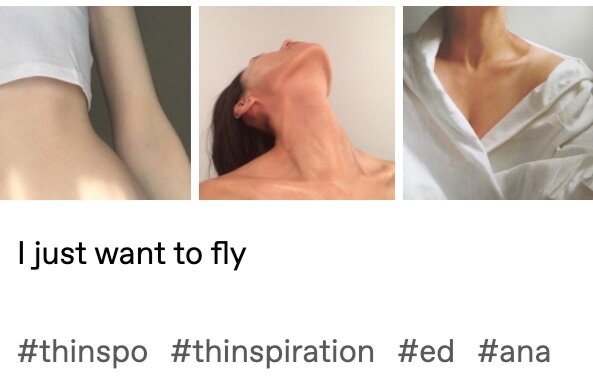

Image courtesy of @grunge-a on Tumblr.

When it first aired in 2007, it immediately became clear that the British series Skins resisted a manicured glimpse into adolescence, one that often characterized TV shows in the early 2000s. Compared to the gaudy extravagance of Gossip Girl or the upper class melodrama of The O.C., Skins navigated both the mundane and the extreme with an agility that amounted to a more precise portrait of the teenage experience. Beyond the overdone tribulations surrounding high school infatuations and parties, the teenagers in Skins grappled with parental abuse and domestic instability, confronted and explored their sexualities, and frequented hospitals for eating disorders and overdoses. While traditionally sanitized in other forms of media, these narratives gained authenticity throughout Skins’s seven seasons, all of which unflinchingly revealed the inevitable “hangover,” as Rebecca Nicolson claims, following the “party.”

At the time, Skins was largely unique in its treatment of adolescence. Teeming with graphic depictions of nudity, substance abuse, and self-harm, the series attracted a wide spectrum of reactions that slid between outrage and admiration. Once it premiered on MTV in 2011, the American adaptation of Skins elicited accusations of child pornography due to its sexual content, prompting companies such as General Motors, L’Oréal, and Taco Bell to withdraw their advertisements from the program. After only one season, the adaptation was cancelled, accompanied by a statement from MTV, “Skins is a global television phenomenon that, unfortunately, didn’t connect with a U.S. audience as much as we had hoped.” Regardless and perhaps by virtue of its provocative tenor, Skins captivated younger audiences, most of whom gravitated toward its ambitious and, in some ways, relatable portrayal of what it meant to be a teenager on the brink of adulthood. But, apart from “enabling youth to rejoice in the fantasy of their corruption,” as Troy Patterson writes, Skins forged an unexpected but critical avenue through which to reconceptualize a myriad of taboo topics.

Fourteen years after the original debut of Skins, sexuality, drug use, and mental health are all approached with an increased sense of transparency and nuance. Boasting tremendous popularity—accumulating over 2 billion total downloads from the App Store and about 1 billion active users monthly—TikTok has situated itself as the primary platform upon which our generation negotiates the shifting vocabulary, attitudes, and conversations relating to stigmatized subjects. In its capacity to meditate upon mental illness in particular, TikTok facilitates raw, candid, and humorous content that tonally mimics Skins, unearthing rather than subsuming personal accounts of hardship and vulnerability. Although generating possibilities for advocacy and community-building, TikTok’s mental health content nevertheless betrays a continued preoccupation with suffering as the metric not only for individuality but for authentic expressions of mental illness.

This may seem familiar. In a popular Tweet, Tumblr is compared to a whale carcass that, as it “drifts down to the bottom of the ocean,” provides essential sustenance to the inhabitants of the benthic zone despite “never [being] seen alive before.” Haunting the wider “Internet ecosystem” as a spectral corpse, Tumblr’s undeniable impact envelops TikTok, informing the platform’s understanding of mental illness. While largely challenging Tumblr’s infamous glamorization of mental illness, TikTok remains suspended upon a threshold, one that thinly separates productive honesty from competitive agony. Many have already highlighted the similarities between Tumblr and TikTok, though mapping mental health and its trajectories on both platforms seems to deliver us at a moment in which recovery, from what I’ve encountered, contradicts a genuine claim upon mental illness. On TikTok, it seems that content destigmatizes mental illness as much as it insists upon a proficiency in suffering. Now, nearly fifteen years after the debut of Skins, discussions surrounding mental health have undergone minimal transformations across Tumblr and TikTok, regardless of outward gestures toward awareness.

Tumblr and the Aesthetics of Mental Health

Eyes sunken and smudged with mascara, Lana Del Rey emerged from a cloud of cigarette smoke in 2012 not as a feisty, energetic starlet but as a “sad girl.” Unlike other pop songs that flooded the radio at the time, Lana’s music resigned itself to droning narratives that were destined for tragedy. “Summertime Sadness,” included in her 2012 album Born to Die, epitomized the forlorn lyricism and muted, grainy imagery that tended to accompany Lana’s music videos. Though its 409 million plays on Spotify is a testament to its popularity, Summertime Sadness, among many other songs, attained mythic proportions on Tumblr during the early 2010s. In GIF sets, image edits, and text posts touting her lyrics, Lana gracefully swept across Tumblr and, in the process, reimagined “sadness.”

Content that popularized mental illness overpopulated Tumblr long before Lana introduced an additional mode through which to express sadness on the blogging platform. Previously lacking chat features or post replies, users on Tumblr primarily proliferated content through reblogging, a form of “signal boost[ing]” that “make[s a] post appear on your blog” without mandating any direct user interaction. As an “asocial” platform governed by “content-based interaction,” Tumblr possesses a unique faculty for anonymity when compared to other popular websites such as Facebook or Instagram. Relieved rather than limited by this “asocial” anonymity, users candidly discuss mental illness and adversity through their own posts or by reblogging relatable content. As reflected in an interview conducted by the Ringer, “I could talk more openly to a group of strangers than I could to people I had to face every day and, I think, worry about me.” Between 2011 and 2015, blogs dedicated to eating disorders, self-harm, and other mental illnesses maintained a significant presence throughout the platform, all of which provided communities in which to find support and peers undergoing similar experiences.

What is lost in this portrait of solidarity, however, is the content that not only packaged but fetishized pervasive turmoil and suicidality. GIFs of teenagers self-harming overlayed with dismal musings (“so it’s okay for you to hurt me, but I can’t hurt myself?”), images of emaciated women above dietary laments, and mood boards featuring teary eyes not only prevailed but flourished on the blogging platform. Before Tumblr drastically curtailed this content in 2012 and again in 2015 with the Post It Forward initiative, graphic depictions of self-harm, eating disorders, and other symptoms of mental illness circulated with ease, as afforded by Tumblr’s reblogging system and its proclivity toward visual mediums such as GIFs. This online “cultivation of sadness,” as Anne-Sophie Bine describes in a 2013 Atlantic article, proved “easy to join,” where any user eager to “advertise their suffering” could “pair images with a quote about misunderstood turmoil...and be gratified.” On Tumblr, mental illness collapsed into uncensored yet artistic exhibitions of “self-loathing under the pretext that it is beautiful, romantic, or deep,” evidenced by the consistent aesthetic that many of these posts assumed. While much of this content certainly conveyed immense interior and physical suffering, it nevertheless embraced fetishistic articulations of mental illness in which “evok[ing] negative emotions through art…put psychological torment and beauty on the same page,” as Bines continues. Beyond these rawer expressions of “psychological torment,” GIF sets containing bleak scenes from, for example, Skins or Lana’s music videos similarly produced a slippage between clinical, ordinary, and artistic suffering, constructing what Dr. Mark Reinecke, chief psychologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, describes as “reverberating echo chambers...that potential negative feelings.”

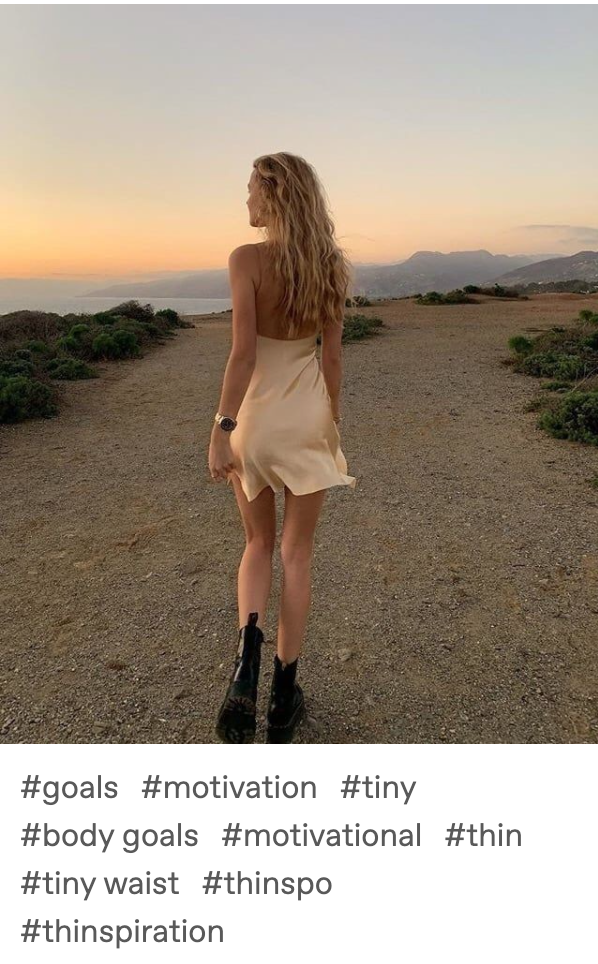

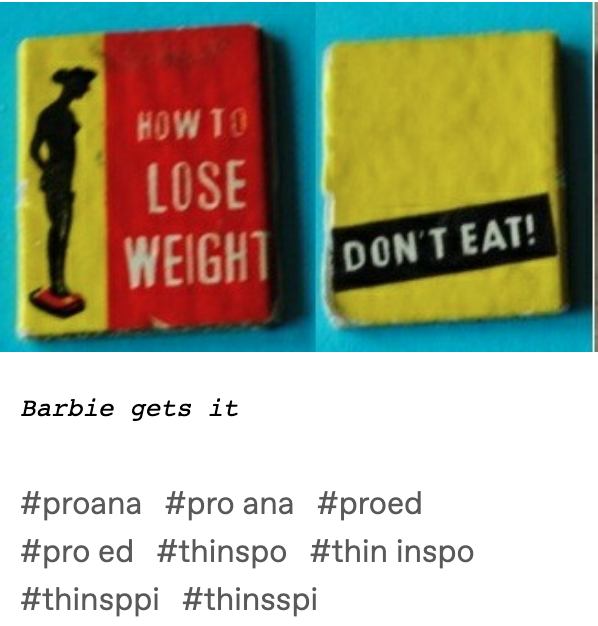

Ricocheting against these digital “echo chambers,” content that idealized anorexia (pro-ana) and bulimia (pro-mia) ravaged Tumblr, overwhelming hashtags, user feeds, and blogs. #Thinspiration, or #thinspo for short, established itself as one of the most infamous avenues through which to access pro-ana and pro-mia content on Tumblr, publicizing unhealthy weight loss regiments and images of thin women. Unlike other platforms such as Instagram and Facebook that actively censored and subsequently “remove[d] relevant hashtags from its search results,” Tumblr instead assumed a “blog-by-blog basis approach.” Tangled within this web of blogs, all of which could choose to forgo hashtags altogether while reblogging or posting content, Tumblr primarily relied upon users or staff members to report blogs featuring harmful content. Confronted by individual blogs, graphic #thinspo images of emaciated bodies, and text posts outlining daily calories and diets, Tumblr remained “replete with triggering and graphic [content].” As recently as 2015, pro-ana content was almost five times as pervasive in terms of unique users when compared to pro-recovery content, according to a study produced by the Georgia Institute of Technology.

In 2012, Tumblr began to modify its previously loose policies on “blogs that actively promote self-harm,” implementing PSA pop-up windows on “search results for keywords” such as anorexia, bulimia, purging, and thinspo. “Joking that you need to starve yourself after Thanksgiving is fine,” the policy reads, “but recommending techniques for self-starvations or self-mutilation is not.” Today, however, the “Everything okay?” PSA does not appear when searching #thinspo or #pro-ana. Instead, we are welcomed, yet again, by “image-rich graphic and triggering content around internalization of thin body ideals.” Despite various efforts to curb the “maintenance of anorexic lifestyles,” Tumblr users continually evade these policies through misspelled hashtags as well as through the blogging platform’s decentralized reporting system, one that emphasizes user accountability and initiative.

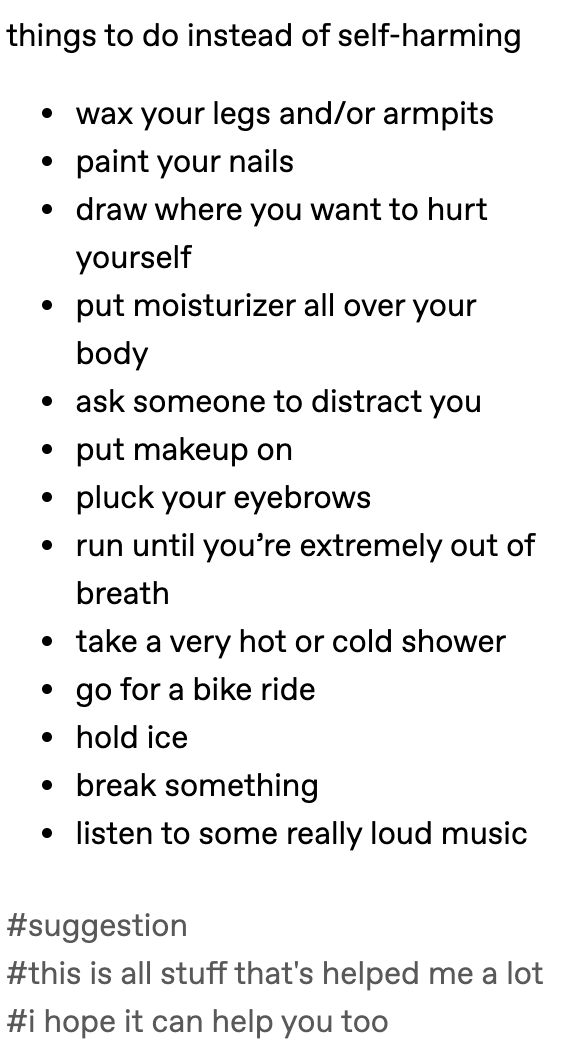

While regulated far more rigorously than pro-ana or pro-mia, self-harm accrued a similar prominence on Tumblr before the platform’s 2012 policy modifications. Reduced to, as Bines writes, “practical bite-sized packages,” self-harm predominantly communicated through GIFs and images, all of which produced a disarming glimpse into fresh wounds, overlapping slashes, and, in “soundless, looped videos,” the act of self-harming itself. Though diluted through “artistic” or “beautiful” portrayals in some circumstances, self-harm largely retained its graphic contours, resisting the monochrome, angsty aesthetic that epitomized “sadness” culture on Tumblr. In many ways, these uncensored portraits owed their oversaturation to Tumblr’s asociality. In offering a rare sense of anonymity and solace from exterior judgement, Tumblr implicitly carved a digital environment in which to “perform non-normative subjectivities” such as self-harm, according to a 2016 study by the University of Guelph in Canada. Once considered a uniquely “personal, lived experience,” as the study continues, self-harm in particular is no longer contained to singular bodies. Instead, suffering and self-inflicted pain belong to a genre of “digital curation,” one that encompasses self-harm as visual content that extends beyond its “immediate physical context.” On Tumblr, the study suggests, images and GIFs of self-harm were attractive by virtue of their “depersonalized” quality—in a word, self-harm became content, a tool to generate expressions of suffering in one raw snapshot that could be reblogged with ease.

As non-specific content that strained against singularity, these images certainly coincided with opportunities to relate, to forge communities in which to approach and subsequently confront recovery. Despite offering “new [ways] of how to comprehend and represent self-injury,” this content nevertheless depended upon graphic and often triggering depictions of wounds, cuts, and bruises in order to curate suffering. After the implementation of Tumblr’s 2012 policies, users reckoned with the damage that circulating images and GIFs of self-harm could cause others, especially those in recovery. Rather than “direct depictions of self-injured bodies,” self-harm and its attendant suffering became rendered through “reappropriations of popular media content that figuratively represent[ed] emotional struggles,” with images of self-inflicted wounds receiving 10 times less reblogs than images without wounds according to the University of Guelph study. In contrast to #pro-ana and #pro-mia on contemporary Tumblr, searching #self-harm now yields discussions of mental illnesses and accompanying hardship, comparatively muted memes or images in Tumblr’s notable “sadness” aesthetic, and, perhaps most significantly of all, hopeful posts encouraging recovery.

This is not to say, however, that Tumblr entirely succeeded in purging a culture rooted in romantic and expository suffering. The continued preoccupation with either humorously or graphically divulging self-hatred is a testament to this pervasive tendency, both on and beyond Tumblr. While “self-defeating” humor can “make you laugh in the short term,” it can nevertheless potentiate associated “negative thoughts…that then can perpetuate stress…even after the humor,” as Jena Lee, a psychiatrist at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, claims. Beyond this, Tumblr’s popularized understanding of “sadness” largely restricted itself to tragic yet glamorous white women, all of whom were thin and hollowed out by tears. If Tumblr’s idolization of Lana Del Rey did not clarify this phenomenon enough, its insistence upon portraying mental illness exclusively through these personae sustained the racism, classism, and exploitation that defines our psychiatric and psychological institutions. As healthcare continues to be inaccessible to many Americans, particularly in Black and other communities of color, the fascination with the “sad girl” as someone who is white, thin, and tragically beautiful erases narratives of mental illness in those who have been historically marginalized, exploited, and excluded by psychiatry.

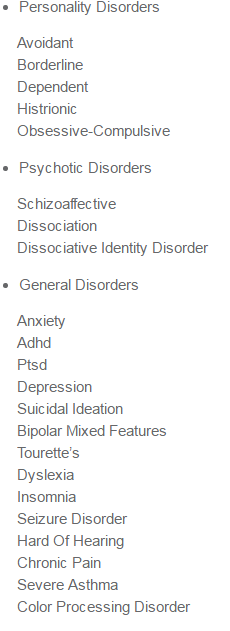

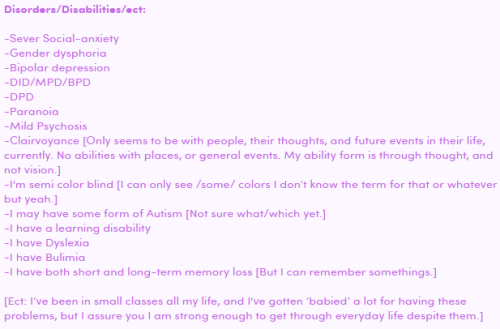

Despite increasing vigilance and familiarity around stigmatized topics, Tumblr wavered between its reputation of glorifying mental illness and its newfound status as a “mental health website.” Having used Tumblr since 2013, I distinctly recall users being “convinced that depression, anxiety, anorexia, and bipolarity [were] ‘cool’ or [could] make you ‘special,’” as Rola Jadayel, a co-author of an influential social media and mental health study, believes. Following Tumblr’s new policies, the culture surrounding mental illness gradually collapsed into one reliant upon oversharing and “collecting” diagnoses. During this time, blogs commonly accentuated “About” pages that featured intimate details about symptoms and behaviors associated with a user’s particular diagnoses, all of which implicitly mitigated a level of Internet safety and privacy. Though underpinning the exclusivity of professional diagnosis in the United States, self-diagnosis similarly contributed to, as Jadayel continues, “an abundance of small sub-communities [engaging in] tragedy olympics.” While I was on Tumblr, I remember users self-diagnosing themselves with bipolar disorder due to occasional mood shifts, with OCD due to feeling anxious about a cluttered room, with multiple personality disorders due to ordinary idiosyncrasies. Formatted as lists, these various diagnoses on “About” pages—whether sincere or exaggerated—often struck me as “collections,” as trophies that rendered certain users “special” in their accumulated suffering. As an adolescent on Tumblr, these impressions vastly altered my perception of the clinical and the ordinary, of what it meant to be “special.” I can only assume that others experienced this as well.

Now, though, my Tumblr dashboard is largely unrecognizable from what once invaded the platform between 2012 and 2016. As users retreated from Tumblr in 2018 due to the “NSFW purge,” the blogging platform has since recovered some of the charm that once made it so alluring. With its shrunken user base and much of its most controversial discourse left behind, Tumblr provides, yet again, a covert environment in which to genuinely engage with content and one another without the burden of being recognized. Though some pockets still devoutly practice Lana’s romantic “sadness” or participate in “tragedy olympics,” Tumblr, at least how I’ve experienced it recently, presents a far more relieving digital space in comparison to Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter. While Tumblr enters a relatively subdued stage, its corpse, like that of a whale carcass, nevertheless continues to drift, providing sustenance to the wider “Internet ecosystem.” Enjoying over 48.8 million users that identify as Gen Z, TikTok has concretized itself as one of the most influential social media platforms through which our understanding of politics, humor, culture, and mental health is formed. For our generation in particular, it has become clear that TikTok has situated itself as the heir to the conversations initiated on Tumblr, conjuring an equally troubling yet altogether disparate vision of mental health.

TikTok and the Culture of Authentic Suffering

In a kitchen, a man is cooking spaghetti bolognese, his young son giggling beside him. Within the first few seconds of the video, the man tosses a sliver of meat toward the camera and, later, crushes a tomato in his fist so its juice bursts across the wooden counter. Over the video by Glen Cooney, known as this.tourettes.guy on TikTok, is a set of bold yellow letters, “COOKING WITH TOURETTES AND ADHD: SPAGHETTI BOLOGNESE.”

Today, as we navigate the sprawling landscape that is social media, it increasingly feels as though there are few platforms that arrive at authenticity. In contrast to the polished content that commands Instagram or Facebook, TikTok displays a rare capacity for genuine, unfiltered expression. Although formally recognized by TikTok as a “mental health warrior,” Glen Cooney’s content on his account this.tourettes.guy endures as a rule rather than as an exception on the platform. While scrolling the endless For You Page (FYP) or hashtags such as #mentalhealth, we witness a user’s daily experience with OCD, a comedic and candid portrayal of taking medication, and a sincere account of recent hardships surrounding anxiety and panic attacks. Distilled into concise but intimate fragments, these various TikToks propel our contemporary discourse around and understanding of mental health, with our generation largely guiding these conversations.

On its surface, the video-sharing platform, similar to Skins, actively interrogates mental health’s historical status as a taboo subject. TikTok’s effort toward destigmatizing mental illness, however, is marked by inconsistencies, all of which are exacerbated by the app’s format. Accompanying the videos that promote mental health awareness is content that, as Morgan Sung writes in Mashable, “pathologiz[e] common traits,” that risk paraphrasing “very real conditions” into “30-second video[s].” A brief examination of TikTok’s mental health subculture yields content that summarizes symptoms of a broad spectrum of disorders, ranging from “high-functioning” anxiety to ADHD. Though at times diagnostically accurate or rooted in personal experience, these videos nevertheless run the risk, as Sung continues, of “encouraging [others] to self-diagnose based on videos that often mislabel widely felt emotions.” With captions limited to 100 characters, a lack of click-through links with the exception of creator bios, and videos themselves being restricted to only a minute, TikTok is, in many ways, unintentionally susceptible to misinformation or oversimplification by virtue of its structural constraints. In TikTok’s #ADHD channel, for example, Dr. Roberto Olivardia, an ADHD psychologist and instructor at Harvard Medical School, claims to have “observed [content] where ADHD gets used loosely…being excited or bubbly does not mean you have ADHD. These videos do a disservice to people who truly have ADHD.” Despite engaging users in productive conversations surrounding mental illness and its symptoms, TikTok remains burdened by its truncated format, one that can quickly lend itself to mental health videos that are fundamentally derived from “superficial characteristics and untrue stereotypes.”

In its tendency to simplify symptoms, TikTok tonally resembles Tumblr, filtering mental illness through the prism of digestible, humorous, or “informational” content. Of course, videos that mention “competitiveness,” “anger over small things,” and “outbursts” as potential symptoms of ADHD or “making things even” and “excessive hand washing” as signs of OCD have the ability to encourage users to seek treatment, equipping people with the tools to critically reassess behavior that may border on clinical. “I think we can do a lot to…get people into mental health treatment,” says psychiatrist David J. Puder, the medical director of the MEND program at Loma Linda University in California, “Knowledge is empowering to people who might not otherwise have access.” What is often overlooked in this equation, however, is how videos framed around lists of symptoms solicit identification with behaviors that, though associated with certain diagnoses, nevertheless appear to be universal or “relatable.” Unlike Tumblr’s infamous romanticization of mental illness, content on TikTok seems to permit an even greater level of relatability, with traits such as “hand washing” or “competitiveness” straddling the boundaries between generalized and pathologized sets of behavior. As Isabel Munson writes, “TikTok is a space designed to create confirmation bias.”

While this “space” can be accessed through hashtags, it’s more effectively curated by the FYP, TikTok’s equivalent of an Instagram Explore page. Enjoying a sophisticated algorithm, the FYP provides its users with an infinite stream of videos, all of which are optimized not only to remain relevant but cater to a user’s pattern of engagement and interests. Within only a few days of gathering user preferences, the FYP is already capable of adjusting itself to its specific audience, delivering content that maintains attention with its “uncanny accuracy.” TikTok’s FYP algorithm, boasting “superior analytics and data harvesting,” seems to “know users better than they know themselves,” as Munson continues. TikTok’s algorithmic promise of categorizing and revealing a user’s identity through FYP content proves seductive, particularly for TikTok’s large population of teenagers and young adults who, unsurprisingly, often emphasizes self-discovery and understanding. Integral to this process of identity formation is, for some, negotiating potential symptoms of mental illness and subsequently achieving clarity with a diagnosis. Through its algorithmic recommendations, however, TikTok performs self-discovery for its users automatically, showing “[users], unprompted, videos about ADHD, autism, and more.” It’s not unusual for comment sections on this style of video to be overrun by users remarking that, “I don’t think I have [that diagnosis], but I keep seeing these videos and it’s making me question.”

As a platform through which mental health resources and knowledge are both increasingly accessible, TikTok and its FYP not only facilitate but empower digital communities that offer support, solidarity, and awareness. Regardless of these productive aspects, the FYP still cultivates the dizzying sense that the videos we scroll past indexes or reflects our “true” character, offering a glimpse into labels we have yet to accumulate or recognize as our own. In contrast to Instagram and even Tumblr, both of which largely rely on direct self-curation, the FYP collapses active and passive identity exploration, inviting users to algorithmically arrive at content with which “relatability” and, perhaps more importantly, identification is most plausible. And, if a user’s FYP hardly deviates in the content it presents, the self and its presumed diagnoses are poised, as Munson writes, to be understood as “static and unchangeable.” Flattened into brief though compelling videos, the nuances of our identities seem to become stable, seem to be expressed through the markers with which the FYP provides us.

To imagine an identity and a diagnosis as “static” often ignores fluctuations in symptoms, behaviors, or, simply, the self. Most of these observations around content and identity curation, however, are made in retrospect and by engaging with the experiences of current users. Over a year ago, in July 2020, I deleted TikTok after nearly five years of using the app and its predecessor, Musical.ly. At the time, I recall that my FYP was flooded with content from TikTok’s mental health subculture despite never having interacted with any specific users, tags, or content. Though some remained purely informational or humorous, most videos assumed a confessional tenor, one that compelled creators to indulge in explicit accounts of their symptoms. That summer, the “rating things my mental illness has made me do” trend fostered the “exhibitionism of self-harm, suicide, depression, [and] self-loathing,” with videos often accompanied with graphic text about symptoms ranging from disordered eating to suicidal ideation. Constantly encountering this content on my FYP evoked a sense of competitive suffering, even as these videos claimed to overshare with the intention of combatting romanticization. While candid narratives did provide an intimate perspective into certain mental illnesses, this content invaded my FYP with an agility that overwhelmed me, that seemed to encourage manifesting the worst symptoms of a condition in order to “relate” to a video. Even content about conditions with which I had previously been diagnosed struck me as alienating, restricting, and accusatory, as if extending a claim upon a mental illness mandates constantly expressing as well as experiencing it in its extremities.

Though this impression may not be universal, the content I inadvertently consumed began to forge a gulf between authenticity and recovery, suggesting that agony is not only an “unchangeable” but essential facet of mental illness. Under this framework, joy or attempts at self-improvement appeared to be antithetical to genuine proclamations of mental illness. In one video, for example, the creator fidgets with an orange pill bottle, the text across the screen imitating quips that are popular among the mental health community, “they only have one pill bottle? Poser! I bet they’re not even mentally ill.” The creator then pans the camera over to an AC lined with multiple pill bottles, the text now reading, “Wow! So many pill bottles! They must be so fucked up. So quirky!” It should go without saying that “only having one pill bottle”—or having none at all—is not necessarily an accurate metric of the severity of someone’s mental illness. What this video accurately punctuates, however, are the fears associated with appearing as an “imposter,” particularly for those that are either in recovery, experience mild to moderate symptoms of their condition, or are only prescribed one or two medications rather than multiple. In certain pockets of TikTok, and certainly on my FYP last year, broad spectrums of symptoms are reduced to their highest octaves, at times neglecting the significance of recovery or the disparate expressions mental illnesses may assume.

Perhaps TikTok’s tendency to overshare the grittiest aspects of a mental illness is similarly rooted in the desire for genuine entitlement or outward validation. One strategy for combating these anxieties, as Anna Gradin Franzén and Lucas Gottzén of Stockholm University found in a study on self-injurious behavior, is to “write detailed descriptions of [one’s] anxiety, diagnosis, therapy sessions, or time spent in treatment centers. This ‘proves’ [one’s] ‘actual’ mental disorder and their entitlement to [symptomatic] behavior.” Perhaps, too, TikTok’s constant categorization and curation of its FYP restrict the capacity to visualize much beyond what we encounter, including labels and diagnoses. A few months ago while scrolling Tumblr, I stumbled across a post that, in many ways, summarizes what I often witnessed during my time on TikTok,

Every few days I see some tweet…saying “I just found out that __ is a symptom of trauma” and it’ll be like getting shivers or rewatching movies…I can’t imagine what seeing that stuff all the time would make me think if I was a teenager. At an age when you’re clamoring so much for identity it seems like we’re encouraging young people to identify with suffering a little too much.

As a platform driven by engagement and confirmation bias, TikTok relies upon content that summons relatability, that allows its users to attain a greater affiliation to the labels with which they gradually or already identify. When suffering and graphic oversharing determines this identification, it increasingly seems impossible to progress toward recovery, at least without sacrificing a critical dimension of our individuality: our symptoms.

Progressing Toward “Okay”

In a personal essay mapping her relationship with mental illness and recovery, Hanna Brooks Olsen writes, “when you’ve spent most of your life identifying with and even clinging to the worst of you, the most painful of you, it makes being well and healthy feel an awful lot like giving up.” Interrogating the “most painful of us” tends to haunt our trajectory toward self-discovery, forcing us to constantly reflect upon and reevaluate ourselves. Our suffering, though, can also be seductive and familiar. It can grow comfortable and inseparable from our conception of ourselves. It can, as Olsen insists, induce “clinging to the worst of us.”

Today, social media serves as one of the predominant modes of self-curation, granting us access to endless digital communities, subcultures, and users with whom we may share experiences. Through the digital content, connections, and environments we consume and actively produce, we continually play with various labels, tease out affiliations, layer our identities. On social media, especially those with extensive anonymity features, we are afforded the rare opportunity not only to curate but to discuss ourselves without ignoring stigmatized topics. In these ways, social media platforms such as Tumblr and TikTok are essential tools of connectivity, individuality, and expression.

As with nearly any cultural or digital phenomenon, though, Tumblr and TikTok are not without their contentious underbellies, both of which, at times, eclipse their productive attributes. Mostly originated on Tumblr, the preoccupation with authentic suffering has ebbed and flowed in its popularity, though it hasn’t been entirely eradicated. Despite contending with these attitudes, TikTok is still conducive to glamorizing the “worst of us,” the “most painful of us.” Similar to Tumblr’s dashboard and tags in their earlier iterations, TikTok’s FYP can also easily slip into graphic depictions of mental illness, most of which insist upon suffering and substantial symptoms as genuine expressions of a diagnosis. And, while created in the effort to dispel misconceptions about mental illness, much of this content may trigger its viewers, especially on the FYP where curated videos are “almost impossible to avoid.”

This isn’t to say that candidly discussing symptoms of mental illness can’t be constructive, both for those sharing as well as for those reflecting. It is to say, however, that destigmatizing or challenging sanitized portrayals of mental illness shouldn’t necessarily depend upon competitive suffering, upon the sense that recovery is alienating. While using TikTok last summer, I’d begun steps toward self-improvement following a long period of struggling with various symptoms. Rather than being met with content that discussed recovery or symptom management, I scrolled an unfathomable amount of videos that overshared symptoms and subsequently accused those unable to “relate” with fraudulent behavior that, in turn, romanticized mental illness. These videos didn’t prompt me to seek treatment; instead, I strived to be worse. I retreated into the “most painful” of myself, the “most painful” aspects of my diagnoses in an effort to extend what I believed to be a genuine claim upon them. Suddenly, the videos on my FYP increasingly resonated with me, stamping me with labels that, at the time, felt so distinct and individual that I feared what would happen once I didn’t experience the same intensity in my symptoms.

In reflecting upon mental health subcultures on Tumblr and their later development on TikTok, I don’t seek or even hope to present a solution to what I’ve come to understand as an overidentification with suffering. Similar to symptoms, the solution is one that is deeply personal and unique to each person. What the trajectory of mental illness on Tumblr and TikTok does reveal, though, is the pervasive gulf between recovery and the self, and how suffering is expressed as content and as an extension of identity, whether this identity be deemed “cool” or abnormal. On Tumblr, this persona was imagined as glamorous, whereas on TikTok it is an emblem of genuine agony that distinguishes users from others. Having used both platforms, I can’t determine which is more destructive. Perhaps it doesn’t matter. Perhaps it’s adequate to acknowledge that our relationship with mental illness requires care and consideration both of ourselves and of others, particularly when symptoms or experiences do not neatly align.

There is an episode of Skins that depicts Cassie, a prominent character in Series 1 and 2, years after her struggles with anorexia and other mental health disorders. Though initially feeling disempowered in the absence of her eating disorder, Cassie and her self-improvement are the subjects of the episode Pure, originally airing in 2013. Throughout the feature-length, two-part episode, Cassie does remain afflicted by certain ingrained behaviors and symptoms, though is nevertheless portrayed as “more grounded.” In Part 2 of Pure, Cassie’s father allows her younger brother to move in with her, a stark contrast to Cassie’s repeated hospitalizations in Series 1 of Skins. At the episode’s conclusion, Cassie watches as her brother receives a haircut, telling him that, and perhaps meaning it for one of the first times, “everything’s good.”

While cult classics such as Skins introduced multiple taboo topics into mainstream discussions, social media is poised to sustain much of them. As Tumblr and TikTok, among other platforms, continue to refine their understanding of mental illness, it’s clear that a greater nuance is gradually being developed in pockets of mental health subcultures. Within these digital communities, we can admit that “everything’s good” while simultaneously maintaining our affiliations with our previous or current symptoms. Both on the Internet and beyond it, we are increasingly able to express joy without abandoning the past, or the diagnoses, that are integral to who we were and who we have become.

Resources

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline | 1-800-273-8255

Swarthmore College Talkspace | talkspace.com/swarthmore

Swarthmore Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) | 610-328-7768