Bo Hu's An Elephant Sitting Still: A Distressing Portrait of Societal Asystole

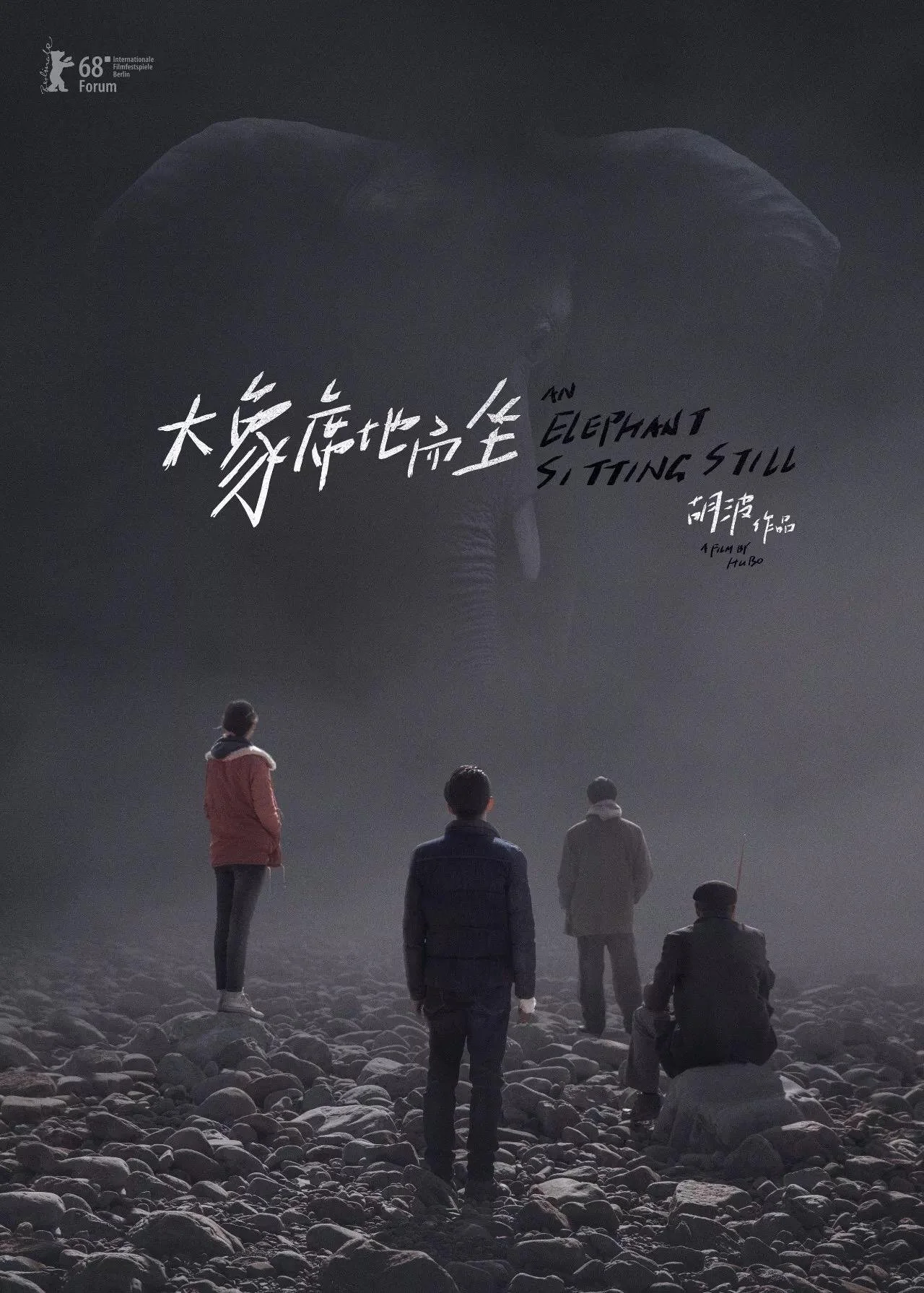

Image courtesy of amazon.com.

Bo Hu’s cinematic masterpiece An Elephant Sitting Still (2018) is a sparse yet impactful social commentary on those who slip through the cracks, telling a scathing narrative rife with addiction, chaos, obsession, death, distraction, and the loss of empathy in the modern world. Released in 2018 and overshadowed by more popular films–such as Burning (Lee Chang Dong, 2018) and Hereditary (Ari Aster, 2018), An Elephant Sitting Still, I believe, deserves more viewership and attention in the Western world. Despite winning more than ten awards across countless indie film festivals, and a notable number of awards at the Berlin and Hong Kong International Film Festivals, including the FIPRESCI and Audience Choice awards, the film’s popularity has barely increased – perhaps due to its length. That said, there is more than enough substance – both cinematically and philosophically – within the film to make its relentless four-hour runtime worthwhile.

But first, a quick (and spoiler-free) plot summary. An Elephant Sitting Still covers one day in the life of four people living in a modern Chinese city. The story of a circus elephant who sits alone all day as circus-goers poke, prod, and bully it, intrigues the four main characters, who are all struggling with recurring depression and financial burdens: one character is involved in an affair turned suicide; another in a school bullying incident; the third, facing his own mortality in a nursing home; and the fourth worries about her future after the closure of her school. Through intertwining events, storylines, and motifs, the four characters all find themselves in search of a way to visit this elephant – the mythical being who can take incessant abuse without any reaction. The journey throughout their lives, in and out of the back alleyways of an urban hub, hooks the viewers until the very end, which is notable as well. A powerful testament to the world of the movie becoming that of the viewers by the end of the runtime, the film’s conclusion was billed by prolific movie reviewer Justine Smith as “one of the greatest in contemporary film history” (as per a Roger Ebert review).

In regard to why a viewer might choose to undergo this exhausting movie experience and subject themselves to representations of some of the most deplorable aspects of the human condition ever seen in cinema, the film presents countless reasons. Indeed, its depictions of what happens to a failing society are numerous and multifaceted, and reveal themselves in specific reflections and cinematic techniques.

For one, the film uses certain cinematographic techniques to depict those with depression, whose surrounding environment is reduced to mere “background noise”– a quiet and often ignored hum that is lost in the mental din that often accompanies misery. Without a doubt, the most important voice in a work of cinema is that of the camera. It can speak in a way the characters cannot, a forced field of view through which an audience member must gaze; it has complete control over the environment. A very noticeable visual technique that is used by cinematographer Fan Chao is what I term “intentional blurriness”: the most common shot in the movie, it is a two-person shot with one subject situated around one foot from the camera and the other situated well over fifteen feet away. Notably, the camera’s focus never strays from the subject closest to it, creating the constant illusion that everything occurring outside of the main subject’s immediate personal space is simply “background noise.” Even shots meant to establish an environment are focused on a person’s face, demonstrating that the film’s environments serve only as white noise for individuals who are trapped in depression or inner turmoil – turmoil that can never be released from the focus of the camera. In comparison with classic cinematic techniques, wherein those who are speaking are given focus priority, this film feels strangely askew. The people in the film feel scrutinized and surveilled, which fuels their need for escape. In the modern day, especially during and coming out of the global pandemic, when the entire outside world can feel like an unbroken loop of background noise that is devoid of meaning as we stare into our computers, this movie is more apt than ever. Part of the reason An Elephant Sitting Still is so pertinent, and strums the most profound of heartstrings so ably, is that it, in many ways, evades being pinned to a specific time. Its plot and message regarding distraction and the ability to focus amid thrumming and disorientating background noise is timeless. Indeed, its omniscience, in every aspect of the technological life we now live, is powerful and truthful for everyone who watches it, at least to some extent..

In addition to its constricting focus suffocating the characters, the camerawork also conveys a sense of chaos to the audience. Never once is it set on a tripod (until the last few shots), and for the most part, it precariously parades the streets following the characters through their mundane lives. Indeed, I would estimate that 97% of the film consists of 3+ minute-long tracking shots that simply follow a character on a walk, into an elevator, smoking a cigarette, or sitting and waiting for the unknown future – cinéma vérité at its finest. What this engenders in the viewer is a sense of impending chaos. As the characters become like family, and the plot becomes our own, the inability of the camera to tie down the story to a particular place alarms. It forces viewers to become even more invested in the story, desperately hunting for any semblance of meaning in the shaky shots, drawing in the countless, helpless eyes. This chaotic cinematography is part of what makes this film so alienating yet so enticing–there is a sense that the chaotic and uneasy emotions of the characters contained within the film leak out into the cinematic techniques themselves and express themselves to the viewers viscerally. Indeed, the film stands as an absurd stage on which profound commentary on the imperfections and chaos of the human race can perform in the grotesque.

The final reason this film is so profoundly moving is its reflections on minimalism. Although the film is shot in color, another very noticeable visual aspect of the film is its greyscale. Set in the urban Chinese city of Shijiazhuang, the buildings block all sources of balmy light, and the sun never makes an appearance, always frustratingly obscured by the ominous dark clouds. One of the many reasons that watching this movie is an exhausting experience is that the viewer has to hunt for any semblance of warmth. After finishing this film, every other movie looks cumbrously colorful. In the simplest sense, An Elephant Sitting Still serves as an antidote to the multi-million dollar technicolor franchises which output movies that rely on visual effects alone rather than focusing on internal aspects like character development. An Elephant Sitting Still is a starkly minimalist piece that may be exactly what this overly consumerist world needs. Instead of serving up twists, turns, and action sequences like oven-ready meals, it makes you wait. You must sit through a five-minute tracking shot of someone smoking a whole cigarette to get any semblance of meaning for the scene. This may seem arduous, but, in reflecting on this film, I believe this slowness and mindfulness (anti-impulsiveness, if you will) is exactly what we all need in this world of notifications, buzzing, beeping, and appointments.

The fourth reason this film deserves attention is its social awareness. Tragically, Bo Hu committed suicide very shortly after completing the film. Indeed, William Gaddis asks in his magnum opus, The Recognitions, “what’s any artist but the dregs of his work? the human shambles that follows it around.” Thus, Bo Hu’s legacy is inextricably linked to that of his work, and An Elephant Sitting Still represents possibly the most intimate look into the workings of his mind. It is critical, then, that one considers Bo Hu’s reason for making such a movie. Bo Hu evidently suffered from depression, and many view An Elephant Sitting Still as his suicide note – a final, sobbing lament to the world he was about to leave. For those of us who are interested in large-scale change and progress in society, the most important perspectives to consider are of those who are neglected – a group including both Bo Hu and all the characters included in his film. Simply put, in terms of a complete portrait of the world, this film is one of the most pertinent ever made.

I hope I have not discouraged anyone from watching this movie – I actually intend to encourage quite the opposite. Indeed, despite (in conjunction with, rather) the upsetting subject matter and distressing plot, the film itself retains its capital-M Masterpiece status easily. I strongly believe, even in my worldly naiveté, that this film is a very necessary piece of social commentary. The depressing nature of it (and its story) only serves those purposes of social commentary more sincerely. This film, more than any other I’ve seen, is the most intimate and accurate portrait of a society undergoing a heart attack, a lethal asystole. It is a severe indictment of those at the top who fail to understand the problems of those at the bottom, and a desperate plea aimed at those who can act on, and cure, society’s ills. An Elephant Sitting Still is available for rent or purchase on Amazon Prime Video. And I can promise you, you’ve never seen a movie quite like it; any film you watch after will feel incessantly shallow.